New Covid-19 response brief from the OECD.org

Link to the original file by OECD is http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-crisis-response-in-central-asia-5305f172/

Overview

The global COVID-19 pandemic is having a significant negative impact on the economies of Central Asia. Trade has been severely disrupted, healthcare systems are coming under strain, and consumption and investment are plummeting. Governments in the region have started to make serious interventions to support the liquidity of households and businesses. The crisis is affecting key drivers of growth in the region, including migrant remittances, oil and mineral exports, and the service sector. Relatively undiversified structures of production and export, along with the high level of informality in some countries, will exacerbate a number of challenges that arise as governments respond to the crisis. Governments in the region are responding at different speeds and scales, with a number implementing short-term public health, monetary and economic policy measures, and some calling for emergency assistance from international partners. While a new set of short-term economic measures should be considered to help with the immediate effect of the crisis, overdue structural reforms to the business environment and competition will be crucial to long-term recovery and resilience.

1. Economic impacts in Central Asia

The economic impacts of COVID-19 challenge government capacities in both OECD and emerging economies

The outbreak of COVID-19 has required governments to move rapidly to expand the capacity of their healthcare sectors and cushion the economic effects of containment policies and their effect on demand. First estimates by the OECD suggest a decline in the level of output equivalent to 2 percentage points of annual GDP for each month that strict containment measures (e.g., restrictions on personal mobility, public services and business operations) remain in place. If the shutdown lasted for three months, with no offsetting factors, annual growth could be between 4-6 percentage points lower than otherwise. Of course, the ultimate impact on annual GDP growth will depend not only on the magnitude and duration of national shutdowns, but also on the extent of reduced demand for goods and services in other parts of the economy, and, critically, the speed at which fiscal and monetary policy support takes effect. Nonetheless, it is clear that the crisis will weaken short-term growth substantially (OECD, 2020[1]).

Supporting measures need to aim at sustaining household income, business activity, and the macroeconomic fundamentals to allow for a quick and sustainable recovery. These measures imply substantial costs to public finances, while the cost of inaction would be even higher since it would entail a long-term destruction of productive capacity.

- People. Most immediately, governments need to implement public health measures, notably containment and support to healthcare systems. Several OECD countries have designed partial work schemes for businesses affected by the crisis.

- Firms: economic measures to support business activity. The pandemic is having a devastating impact on the revenues and liquidity of businesses and their capacity to comply with tax requirements. Most OECD economies have designed substantial fiscal measures to support firms, through credit guarantee, loans, and tax deferrals, and workers through wage support.

- Macro. Central Banks have injected sizeable sums to support the economy, both through quantitative easing (unlimited in the case of the US Federal Reserve) and through lending support to firms and households: the US Federal Reserve has announced USD 300bn support and the European Central Bank EUR 400bn.

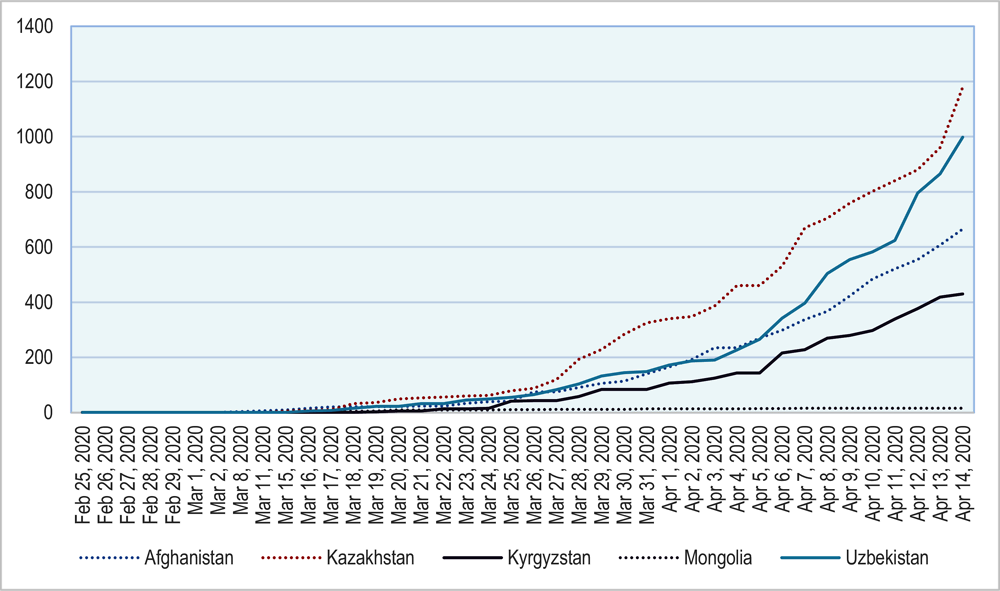

COVID-19 arrived in Central Asia comparatively late

Central Asian countries started to report their first COVID-19 cases in mid-March, with the exception of Afghanistan, which reported its first cases late February. The number of cases has exploded since, following a similar trend to most of the world (Figure 1). Mongolia adopted strict containment measures early, closing all borders, and has so far limited the number of declared cases. As of 14 April, two countries had yet to report any cases: Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

Figure 1. COVID-19 in Central Asia has spread rapidly in the region since the first cases were reported

Graph current as of 14/04/2020

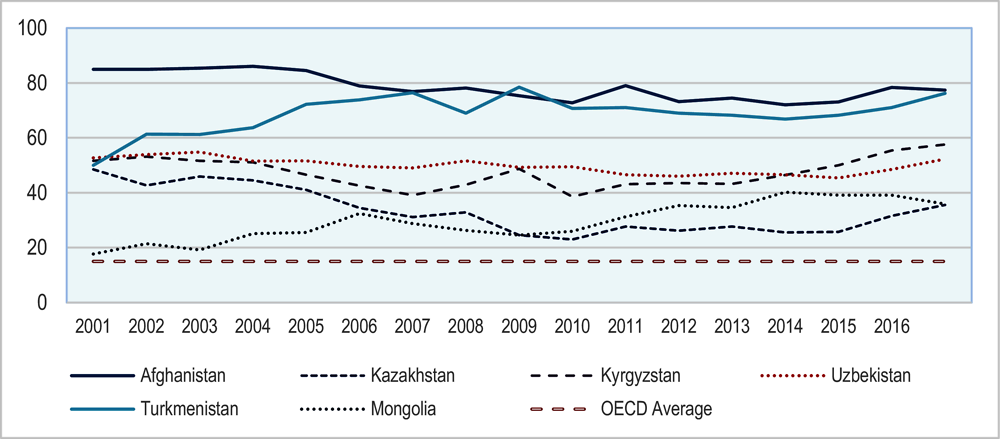

Returning migrants are likely to exacerbate the strain on underfunded healthcare systems

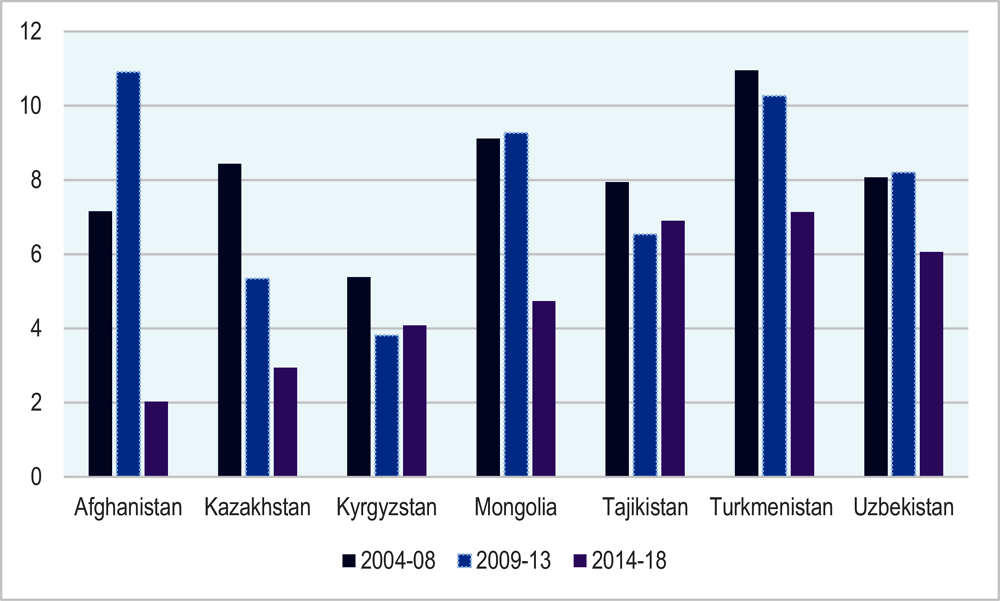

The spread of COVID-19 in Central Asia is likely to put significant strain on the region’s healthcare systems, with the latest data available showing average regional healthcare spending at 6.3% GDP, or about 740 USD per capita at purchasing power parity exchange rates, significantly below the OECD average (WB, 2016). Even in cases where spending has been higher, such as Kazakhstan, healthcare system performance has significantly lagged OECD standards (OECD, 2018[2]). Low levels of government spending have led to an unusually large share of the cost of healthcare being transferred to households, putting further downward pressure on consumption, with Central Asia having some of the highest ratios of out-of-pocket healthcare spending to total health expenditure in the world (Figure 2). Women, in particular, have poorer access to healthcare, due in part to the limited number of female doctors and in part to inadequate levels of provision in many rural areas.

The heavy reliance of some Central Asian countries on labour migration entails additional challenges. Due to border closures and decreased demand for labour in Central Asian migrants’ traditional destination countries, a larger number of migrants will be forced to stay home. This will increase the pressure on local healthcare and social systems at a time when they are under significant stress. At the same time, many migrants may continue working in countries with high rates of infection while not having proper healthcare treatment, which risks reintroducing the virus to Central Asian countries.

Figure 2. With healthcare systems under-resourced, citizens bear the brunt of costs

Out-of-pocket healthcare spending as total of healthcare expenditure (%)

Shrinking budget revenues will limit governments’ ability to respond to the crisis

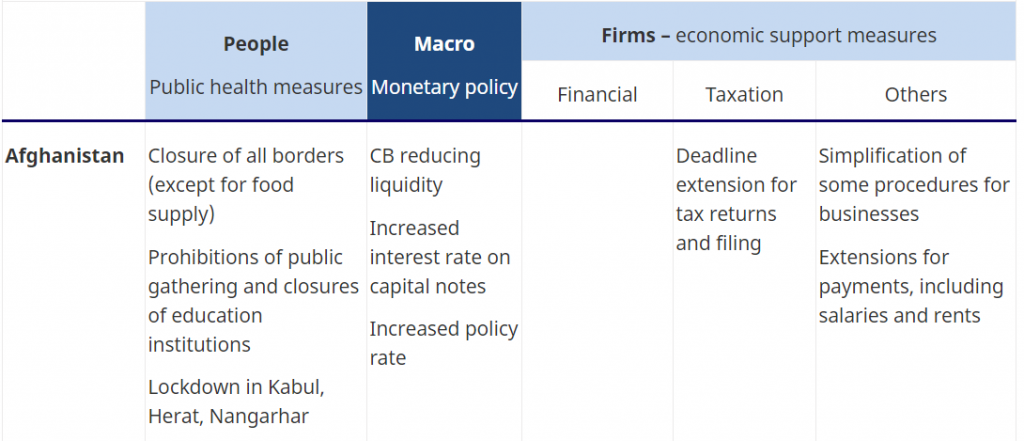

As with the 2008 global financial crisis and the end of the commodity super cycle in 2014-15, when Central Asian economies’ GDP fell more sharply than the world average, it is likely that regional growth will fall significantly, and public finances will come under strain (Figure 3). The shock of the global drop in commodity prices – a trend already being replicated in 2020 – had a particularly strong impact on countries with large extractive sectors. The sharp fall in growth seen in 2016, and the inability of countries to reach pre-2015 growth rates since, laid bare the limitations of resource-dependent growth models for long-term, resilient development. The combination of reduced export earnings, particularly for hydrocarbon exporting economies such as Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, and significant trade disruptions will narrow the fiscal space for governments to respond, limiting their ability to stimulate local demand, support businesses, and address long-term priorities.

Figure 3. Average real GDP growth rates in five-year increments, 2004-18

The ability of Central Asian countries to implement similar emergency measures to those being undertaken by OECD members is constrained by limited budgets and far smaller scope for public borrowing, particularly in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Fiscal space in these countries is likely to shrink further as the economic effects of the pandemic are felt. Some countries, such as Kyrgyzstan, have already turned to international donors to obtain emergency financing, but it is not clear to what extent such institutions will be able to provide the types of debt-funded direct financial support being implemented by national governments elsewhere.

The drop in global demand for primary commodities is already making itself felt in the region. In Kazakhstan, for instance, the government has had to revise its state budget for 2020, which was based on an average annual Brent oil price of 50-55 USD per barrel – as of April 2020, the price had collapsed to 20 USD (Government of Kazakhstan, 2020[3]). Indeed, while the Novel Coronavirus itself seems to have reached Central Asian states relatively late, they were among the first to feel its economic effects, owing to the initial outbreak in neighbouring China at the start of the year. Chinese imports from Central Asia fell sharply in the first quarter, and PetroChina issued a force majeure notice, cutting planned gas purchases from Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. According to Chinese trade data, January-February imports from Turkmenistan and were down more than 17 and 35% respectively. Trade turnover with Kyrgyzstan fell almost 12%. Given that more than 75-80% of Turkmenistan’s exports have been to China in recent years, the cost to that country is particularly great.1

Efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 will significantly increase trade costs

Being relatively small, and in most cases fairly undiversified, economies Central Asian countries depend heavily on foreign trade, despite the fact that their location and landlocked position imposes higher transport. The ratio of trade turnover to GDP across the region averages 65%, higher than the 58% OECD average (World Bank, 2020[4]). As countries in Central Asia have progressively closed their borders with neighbours and restricted internal movement of people and goods to stem the spread of COVID, value chains have been disrupted. These value chains – as well as the availability of domestic goods and the concomitant question of food security – will be further imperilled by border restrictions imposed by China, Iran and Russia. Not only will lower and more expensive trade have an impact on consumption, but it risks further decreasing the manufacturing competitiveness of a region where connectivity and regulatory barriers already create significant costs.

Falling migrant remittances will further squeeze government revenues

Russia’s decision in March 2020 to close its borders to non-Russian citizens, though subsequently relaxed in respect of citizens of the Commonwealth of Independent States, highlighted the precariousness of many Central Asians’ reliance upon the country for employment. In Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, for example, where the domestic private sector has been unable to provide a sufficient quantity of quality jobs, labour migration has been an economic lifeline for many households, with remittances accounting for around 30% GDP in both countries (World Bank, 2019[5]) (EBRD, 2019[6]). Yet the countries to which labour has traditionally migrated – in particular, Russia and, to a lesser extent, Kazakhstan – are themselves highly dependent on the export of commodities. Recession in such economies will have an impact on the demand for labour, invariably affecting many households across Central Asia.

Support for those in need, especially women, is complicated by high levels of economic informality

High levels of informality complicate government efforts to respond to COVID-19 by reducing the potential tax base and rendering it difficult to gather data or to reach and protect firms and citizens most in need. Where formal businesses may be able to rely on social safety nets or savings to endure the crisis, the same is not true for informal firms. Government policies may facilitate firms’ access to essential inputs but informal firms may be unable to access these measures. Many informal firms face a difficult choice between ignoring government recommendations in order to sustain income, putting themselves and others at risk of infection, or following government recommendations but facing severe hardship.

Past crises have also shown that women, in particular, suffer from the effects of a crisis. In Europe and Central Asia, women perform on average twice as much unpaid care work as men, a burden currently heightened by school closures and food insecurity. The ILO estimates that almost half of women in the workforce (including agriculture) operate in the informal sector, which entails limited insurance coverage, social protection and access to healthcare. Globally, women make up 70% of workers in the healthcare and social sectors, which puts them at a heightened risk if asked to continue their work during the pandemic. Central Asian governments will therefore have to streamline gender in their response mechanisms and include dedicated programmes addressing both short- and long-term needs of women, particularly the most vulnerable, such as additional cash transfers and benefits for households responsible for fostering children and taking care of elderly or disabled persons.

2. Policy responses

Virtually all Central Asian governments have prepared and implemented specific policy responses to address the health situation and fight the economic consequences of the pandemic (Table 1). Several have designed dedicated national plans or funds to gather and channel financial flows, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Uzbekistan.

Most of the region’s governments have developed specific measures aimed to support business activities. They have increased the liquidity and credit lines for businesses through dedicated funds and commercial banks. Some have also supported deferral of loan repayment from banks. Another policy response relates to taxation, with governments postponing tax declarations, deferring tax payments, suspending tax audits or exempting firms from social contributions, among other measures.

The drop in commodity prices and exports, as well as the uncertain economic outlook, have led central banks in the region to adopt differing policy responses. The National Bank of Kazakhstan adopted an initially restrictive monetary policy, increasing its policy rate, while supporting the currency against over-depreciation, in an attempt to prevent a surge of pass-through inflation. By contrast, the central banks of Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan have eased constraints on banks’ liquidity ratios and lowered policy rates in an attempt to channel additional liquidity to the economy. Kazakhstan followed suit in early April. Uzbekistan has adopted a third approach, allowing for targeted and eased refinancing operations of commercial banks, while keeping its policy rate unchanged at a record high.

Several countries have called for emergency financial support from international partners and have received emergency funding to mitigate the immediate economic impact of the COVID-19. For instance, Kyrgyzstan has been the first country to benefit from emergency support funds from the IMF.

Table 1. Overview of the main announced measures in Afghanistan as of 14 April 2020

3. Policy options for Central Asian countries

People: Containing the outbreak and protecting employment

Most Central Asian countries have taken strong measures to protect the health of the population and contain the pandemic, including quarantines, lockdowns and awareness campaigns. It is important that all governments acknowledge the realities and challenges of the pandemic, and take immediate health and containment policy responses such as workplace social distancing, school closures, bans on public gatherings and mobilisation of healthcare capabilities, including the mobilisation of inactive health professionals and the provision of spaces to diagnose and treat patients safely (OECD, 2020[7]).

To respond rapidly to the supply- and demand-related shocks that businesses face, OECD governments have reacted with short-time work schemes (STW), introduced after the financial crisis in 2008. Through STW, governments provide public income support to those with reduced hours or complete suspensions. Firms make use of STW to avoid laying off their staff or closing down. France, for instance, simplified its previous STW schemes to make them available to its entire workforce, replacing up to 84% of their wage, coupled with enforcement mechanisms. However, some business closures remain inevitable. OECD countries have extended the access to unemployment benefits for non-standard recipients, such as self-employed workers, and considered one-off payments. Australia and Italy offer lump sums to those affected by the crisis who would usually have not been eligible to unemployment benefits. Delivery means were updated: applications can now be filed by phone or digitally. Governments have also introduced temporary deferments of utility or rent payments, and inhibited evictions (OECD, 2020[8]).

Across Central Asia, governments are ordering confinement measures, paralysing most of the economy, both formal and informal. There is thus a need to create a social protection floor for the entire population to make sure that citizens have a safety net on which to rely, by guaranteeing access to healthcare and basic income (OECD/ILO, 2019[9]). In Central Asia, which already faces challenges with public service delivery, administering this type of programme across geographically fragmented countries remains intricate. Such measures must be adapted to local conditions. Morocco, for example, has expanded its unemployment scheme beyond the formal sector. Payments occur through mobile payment platforms, also allowing collection of data on the informal sector. To finance the scheme, the government set up a Special Fund for the Management and Response to COVID-19, financed by donations, IFIs and state funds.

Apart from their economic costs, containment measures – in Central Asia no less than in other regions of the world – may bring about lasting changes in state-society relations. Measures put in place to contain the pandemic may have long-term negative effects on the space in which civil society operates. In the context of the current crisis, this has raised concerns around the world about the extension of public surveillance and the perceived use of the crisis in some countries to tighten political control and restrict civic space. More broadly, the pandemic risks overburdening countries’ basic governance functions, which could threaten socio-political cohesion, exacerbate corruption, unsettle relations between central and sub-national governments, and transform the role of non-state actors.

Firms: stimulating liquidity, financing and digitalisation

Governments and central banks play a crucial role in providing liquidity to businesses, in particular SMEs, which are more vulnerable to financing fluctuations and therefore less prepared to withstand a sharp disruption. Central banks can provide funds to banks and nonbank financial companies, to foster lending to financially distressed businesses, while several Central Asian governments have designed anti-crisis measures to stimulate business activity, focusing largely on taxation and SMEs. Some of these measures are in line with OECD countries’ responses and could be more broadly applied in Central Asia. They include: deferral of loan repayments, especially for loans disbursed by SME funds; the creation of loan distress funds, as was done in the United States, possibly financed by the state and IFIs; and the development of emergency credit products and guarantees, preferably to be channelled by SME agencies in partnership with banks, as has been done in France.

Some Central Asian countries and most OECD members are providing tax relief to businesses and households. They have deferred the payment of social contributions (Turkey), extended deadlines for filling tax returns (France, the United States), waived or deferred payment of certain taxes and suspended tax audits.

OECD countries are conducting massive awareness campaigns to inform businesses about risks and possible mitigation measures. Campaigns have been rolled out in co-ordination with business associations and SME agencies, often heavily relying on digital and social media channels. The French government, for example, has prepared an operational handbook on protective sanitary measures for delivery companies.

Some programmes have also encouraged digitalisation of communications and activities, including Francedigital in France and programmes to move from physical activities to online business portals in Korea. Across Central Asia, this coincides well with digital priorities and achievements over the last few years. To further promote teleworking in businesses, governments could consider increasing awareness among firms, providing financial support to help SMEs develop teleworking capacities, and collaborating with technology companies to offer SMEs better access to digital solutions (OECD, 2020[8]).

Macro: ensuring immediate monetary response and providing liquidity

Against the backdrop of falling commodity exports, and the grim economic outlook, central banks have provided a first set of measures to support their currencies against over-depreciation, prevent a potential surge of pass-through inflation, and provide liquidity to commercial banks. The magnitude of the slowdown will require a delicate balance between containing inflation and providing liquidity support to businesses and households to sustain activity and consumption. A liquidity crisis could significantly worsen the extent of the slowdown and delay prospects for recovery. However, there is only limited room for manoeuvre: the high degree of informality in Central Asia and the persistent weakness of banking sectors in the region do not allow the transmission channels of monetary policy to function as they do in most OECD economies. Central banks will have to rely on their reserves for any large-scale support measures, which may make the stability of their currencies less robust and limit their ability to manage exchange-rate fluctuations.

Improving regional dialogue and co-ordinate policy reactions

Central Asian governments will have to make sure that essential and emergency-related sectors are maintained throughout the crisis, including healthcare, electricity, utilities and telecommunications infrastructure, as well as food supply and distribution. Particularly with border closures, some Central Asian countries may face challenges with respect to food and utility supply, revealing the stark interdependencies in the region. IFIs and other development partners active in the region have already committed to financially supporting government health responses, including via direct donations to governments. Their involvement may also be required to help manage the effects of border closures.

Long-term measures: improve the overall environment for firms

Not only will the slowdown limit the ability of Central Asian governments to react to the immediate needs of firms and citizens, it risks creating serious fiscal pressure, particularly for countries with large current account deficits and large foreign currency denominated debt. It is essential that in dealing with the immediate social and economic consequences of the pandemic that governments are able to maintain momentum with structural and legal reforms that increase their resilience in the long-term. Governments must therefore be attuned to the demands of the private sector, and undertake the regulatory, policy and investment decisions that supply the conditions for business development on the long run.

4. Country overviews

Afghanistan

Economic overview

Afghanistan has been facing much uncertainty in recent years, resulting from the political crisis, armed conflict and climate impacts. These developments have led to reduced FDI (inflows fell from USD 4.3 bn in 2005 to 0.6 bn in 2018), stark depreciation of the Afghani against the dollar, increased spending including on security, and volatile GDP growth rates. In 2019, GDP growth stood at 2.9%, linked to a recovering agricultural sector after severe droughts at the beginning of the year. The trade deficit remains large, mostly financed by grant inflows. Exports have been increasing at an annual rate of 14.7% with foods dominating the formal export basket. Pre-COVID-19, Afghanistan was facing increasing domestic revenue inflows, largely in line with its plan to become self-sufficient over the longer term. However, with COVID-19 and the U.S. budget cut, efforts of self-reliance through domestic revenue mobilisation look bleak, thus not coinciding with expected reduced ODA figures.

Economic impact

Short-term indicators. Unemployment stood at 39.5% in 2017, and 80% of employment is informal. COVID-19 will have an additional impact on the strained official and informal labour markets, in particular with returning migrants seeking employment and businesses experiencing reduced revenue (some up to 90%) or halting operations. The IMF expects the economy to contract by around 3% this year, following growth of roughly the same magnitude in 2019 (IMF, 2020[10]).

Public finances. Almost half of the state budget is financed by donors, including 37% by the United States. Thus, despite low public debt (7% of GDP), Afghanistan is classified as being at high risk of external debt distress. The costs of containing COVID-19, coupled with the USD 1bn reduction in the 2020 budget and the drop in national revenues are severely squeezing the budget, and the government has announced austerity measures. As the economy is expected to contract in 2020, a cash deficit is expected by mid-2020.

Financial markets. Afghanistan’s formal financial market remains small, as informal practices predominate. Estimates state that the majority of payments occur through hawala dealers, currently affected by movement restrictions, decreasing cash flows and inputs for SMEs. Food prices and CPI inflation have already soared over the past month.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. Afghanistan faced its first COVID-19 case end-February, following a wave of returnees from Iran, who had left in response to the deteriorating economic situation. Herat, bordering Iran, is, together with Kabul and Nangarhar, in complete lockdown; other affected provinces are enforcing partial lockdowns. Some borders to Iran and Pakistan are occasionally re-opened for food imports and returning migrants, with all other country borders closed. Commercial air traffic from abroad has largely been suspended, but internal traffic continues. The government announced the release of 10,000 vulnerable prisoners to slow the spread of the virus. All education institutions have been closed until 21 April, with the Ministry of Education preparing for distance teaching measures. Both the Taliban and the government are implementing awareness campaigns. Several military officers have tested positive, prompting countries to pull out soldiers, despite rising insurgent attacks across the country. Development partners, including the World Bank and the European Union, are re-programming their existing efforts towards humanitarian needs, also aiming to mitigate the fiscal shock. The IMF has approved immediate debt relief to the government. The government has channelled funds towards Herat, feeding into the construction of a 300-bed hospital.

Monetary policy. The central bank has been injecting funds into the currency market and plans to increase its interest rate on capital notes in order to contain inflation and stabilise the currency, as the value of the Afghani dropped by 3% to the USD in the local foreign exchange market. The CB is planning on facilitating operations for commercial banks, by abolishing penalties for late reporting or lower liquidity, and stands ready to provide liquidity to banks as a lender of last resort. The bank is planning to relax asset classification and loan-loss provisioning.

Economic support measures. The Ministry of Finance has extended the deadline for filing income tax returns, and put in place extensions for salary payments, payments to vendors, and rental payments for March and April. The government has promised support to SMEs, particularly in the agribusiness sector. The governmental crisis response is dominated by ensuring adequate food supply, which had been interrupted by erratic border closures and the spring flood season. It is importing essential goods from India and China, and is collaborating with Pakistan to prevent border closures. Kazakhstan, Afghanistan’s largest source of wheat, has agreed to continue its supply. Development partners have announced cash-based assistance to vulnerable groups and direct financial support to MSMEs.

Outlook

COVID-19 arrives at a time of political uncertainty following the 2019 presidential elections, after which two candidates declared victory. The U.S.-Taliban peace deal has not yet resulted in reduced violence, directly hindering medical care delivery to Taliban controlled areas. The population is thus vulnerable, as Afghans have one of the highest shares out-of-pocket expenditures on health in the world and an estimated 14mn may face emergency food insecurity. The government will have to build better health infrastructure, ensure price stability and food security, support its private sector by implementing policies beyond Kabul and the formal sector, and ensure the stability of the formal and informal financial sector to provide liquidity, while containing inflation.

Kazakhstan

Economic overview

After a decade of commodity-driven growth, the combined impact of lower global oil demand and price volatility triggered a sharp slowdown in 2015-16. In 2017-18, the economy recovered, growing at a solid but unspectacular rate of 4.1%, still driven largely by oil output and increases in commodity prices, which underpinned rising domestic consumption and positive spill -over effects on the non-oil manufacturing and services sectors. Growth moderated in 2019 due to stagnating oil production, low foreign investment, and subdued domestic demand. The fall in commodity prices and demand with the COVID-19 outbreak is significantly hitting the growth rate, exports and government revenues, calling for state support.

Economic impact

Short-term indicators. At least 1.5 million people are estimated to be on unpaid leave or have lost their job due to the outbreak of COVID-19. According to official data, SMEs that are most likely to be severely affected (trade, tourism, and catering) employ over 1.6 million workers. Growth for 2020 is expected to fall at -2.5% of GDP, after 4.5% in 2019 (IMF, 2020[10]).

Public finances. The current drop in global demand for extractive goods and commodity prices has already forced the government to revise its state budget for 2020 (Government of Kazakhstan, 2020[3]), with a planned cut of USD 1.25 bn budget spending.

Financial markets. Sovereign interest rates on the 10-year bonds issued in tenge have increased by about 10% since the beginning of March; the value of the associated credit default swaps (CDS) has likewise increased by about 40%. However, one-year default probability has remained stable. Between the beginning of March and 7 April, the tenge depreciated by about 14% against the dollar.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. Kazakhstan declared a state of emergency on 15 March. Exports of key food products have been banned, while imports of food products and freight have been maintained and a cap on food prices introduced. The government has closed all borders to entry of non-citizens, has quarantined the main cities of Nur-Sultan and Almaty, and has put air and train traffic on hold. Educational institutions, public places, non-essential businesses have been closed, and working hours of public transport limited.

Monetary policy. After an increasing its policy rate in mid-March as the tenge came under pressure2, the National Bank of Kazakhstan (NBK) cut it to 9.5% and expanded further the interest rate band to +/- 2%. The NBK also eased refinancing operations for commercial banks. Foreign exchange controls for SOEs have been introduced to support the tenge.

Economic support measures. The government designed an anti-crisis package of 10 billion USD (4.4trn tenge or around 6-7% of GDP) to cushion the economic impact of the pandemic. Measures are to support businesses, in particular SMEs, and households. The state will finance an extension of the social safety net by providing wage and unemployment subsidies, and food baskets to the most vulnerable. Businesses are granted liquidity support, loan guarantees, and temporary tax reliefs to sustain operations and shield employment.

Outlook

COVID-19 has already reduced state revenues and necessitated a significant fiscal response, while further negative effects on trade and industrial production are expected. Given the structural challenges facing the Kazakhstani economy, prospects for resilience will crucially rely on the ability of the social safety net to sustain household consumption, and of the banking sector to provide liquidity to the private sector.

Kyrgyzstan

Economic overview

The Kyrgyz economy has grown at an average rate of 4% since 2014, and whilst growth slowed to 3.5% in 2018, it reached 4.5% in 2019 due to a 15% increase in output from the country’s largest gold mine, Kumtor. The higher earnings from gold exports combined with lower import spending has resulted in the current account deficit narrowing from 12.1% GDP in 2018 to 9.3% GDP in 2019. Remittances from labour migrants continued to support domestic demand and reduce the current account deficit. FDI in non-extractive sectors remains low, with limited investment in the financial and manufacturing sectors. Economic slowdown in Russia will reduce the demand for migrant labour, markedly lowering levels of remittances to Kyrgyzstan. At the same time, lower global demand and trade interruptions will decrease export revenues. Both of these factors will put a strain on public finances, and have already led to government requesting emergency international support.

Economic impacts

Short-term indicators. COVID-19 has already severely affected a major part of Kyrgyzstan’s economy. According to the Ministry of Labour and Social Development, an estimated 1.8m workers are now unemployed out of a total (2019) labour force of 2.6 m, in a country where informal unemployment is high. The IMF currently anticipates a contraction of 4% this year (IMF, 2020[10]).

Public finances. Domestic revenue collection and export revenues have fallen sharply due to reduced commodity prices and border restrictions. The government has estimated losses to the budget in 2020 from this crisis at around KGS 28 bn (USD 330 m). Remittances, which amount to as much as one third of GDP, have fallen by 14%. Kyrgyzstan faces a gap of USD 405m in its balance of payments, with the fiscal deficit to further widen by 5% in 2020. Following the government’s request, the IMF has agreed to provide USD 120m in emergency financing. The government will cut all non-essential expenditures, while seeking to protect critical expenditure items like public-sector salaries, pensions and welfare support, sand the cost of public health and containment measures.

Financial markets. By end March, the Kyrgyz Som (KGS) had depreciated by 20% against the USD since the beginning of the year. The National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic (NBKR) intervened in order to smooth out sharp fluctuations in the forex market. To support the KGS in the local financial market and comply with mandatory reserve requirements, the NBKR has granted loans to commercial banks in KGS, and has sold USD 202 m of foreign exchange reserves as of mid-April 2020.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. The government has declared a state of emergency, with some districts in quarantine and Bishkek under a nightly curfew. All education facilities are closed and local elections are postponed. Mobility across the country is restricted, and large gatherings are banned. Borders have closed, all freight has been cancelled, and foreign nationals face a temporary travel ban. Trade has largely been interrupted, except for essential goods, with health checks and potential quarantine measures for importers. One percent of the annual state budget has been allocated to react to COVID-19, including expenditure on additional medical supply and salaries for health personnel. The government is further co-ordinating with partners in the Eurasian Economic Union to ensure imports for medicine and medical supply.

Monetary policy. The NBKR maintains its flexible foreign exchange regime and limits FOREX interventions to prevent sharp exchange rate fluctuations. It will adapt its monetary policy depending on future currency fluctuations. For the time being, the policy rate remains at 5%. The government has recommended the NBKR to conduct credit auctions in order to provide the banking system with the necessary level of KGS liquidity to maintain lending to the real sector.

Economic support measures. The government has unveiled measures for the business community, whilst simultaneously stating that the scope for action remains constrained by limited finances. The short-term plan (3 months) includes measures to ensure food security (with a preference given to local suppliers) and aims to ease requirements for businesses including: delaying social contributions for 3 months, discounts on renting state property, deferring utility bills, cancellation of tax sanctions and penalties until July. The government further extended the deadline to submit tax declarations for all businesses and has introduced a temporary ban on bankruptcy procedures of businesses until January 2021. The NBKR is co-operating with commercial banks to suspend loan repayments and offer an extension of the moratorium on business checks. The EBRD also offered measures of concessional financing for SMEs and emergency financing mechanisms to guard the liquidity of banks. The Russian Kyrgyz Development Fund has also simplified procedures to facilitate lending to businesses. Despite these announcements, the government has warned that the means at its disposal for the coronavirus response are limited and that support will focus in the first instance on firms that have been hit hardest and that provide most employment, and on vulnerable segments of the population (with food packages).

Outlook

Kyrgyzstan has been severely affected by COVID-19, rapidly depleting public finances and paralysing most of the country’s economy. To counter the effects of the crisis, the government will have to endorse further measures to support the private sector, especially SMEs, and strengthen the social safety net, whilst closely observing monetary fluctuations. Over the long-term, the reduction of the fiscal deficit should remain at the forefront of the government’s agenda, and measures to improve the legal environment for business, formalise business activities and further reduce trade barriers will be needed to ensure sustainable growth.

Mongolia

Economic overview

Growth has been primarily driven by the export of extractive products and has therefore fluctuated with changes in the prices of and demand for these commodities, particularly of copper. Mongolia’s exports remain concentrated in terms of both products and destinations, making the country particularly vulnerable to external shocks. Public finances were hit by the 2015 commodity price slump and pushed the Mongolian authorities to secure a support package from the IMF. The COVID-19 crisis has led to a steady decrease in commodity prices and demand, especially from China, and Mongolia had to stop coal exports for a few weeks at the beginning of the crisis due to sanitary measures, before resuming them. The impact on business activity, exports and tax revenues is likely to weigh heavily on business activity, employment and public finances.

Economic impacts

Short-term employment indicators. According the Mongolian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, two thirds of businesses were impacted by the COVID-19 and more than 8,000 jobs could be lost. This would increase unemployment rate from 8% to approx. 12%.

Public finances. Tax revenues fell by 20% year-on-year during the first two months of 2020. The anti-crisis package has been supported by IFIs, including the ADB and the World Bank. These measures will nevertheless put a strain on public finances.

Financial markets. The Stock Exchange MSE Top-20 Index has fallen by almost 13% since the beginning of 2020, which is less than the main global stock markets.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. Mongolia closed all borders with Russia and China early in the crisis and enforced a travel ban on foreign nationals. Public gatherings have been prohibited and people are required to wear masks in public places. All public places are closed until 30 April while restaurants and bars are operating with reduced hours. Closure of schools has already been extended from 30 April to 1 September. Disinfection campaigns are conducted in the main cities, and control points have been established at the entrances to the capital. Imported food and non-food products are disinfected by public authorities. Coal exports to China have resumed, but carriages are disinfected in a systematic manner.

Monetary policy. The Bank of Mongolia has cut its policy rate from 11 to 10%, then to 9% and expanded the interest-rate corridor to +/-1. The BoM has decided to extend the maturity limit on consumer loans up to 12 months for lenders having trouble in their loan repayments, and has received massive requests for support.

Economic support measures. On 27 March 2020, the government announced a national package of seven measures totalling MNT 5.1trn (1.7 bn) to protect the health and income of people, preserve employment and stimulate the economy during the pandemic. The package backed by parliament on 9 April contains a series of measures, including, but not limited to the following:

- temporary tax exemptions for six months from 1 April, including the waiver of personal income tax for employees, exemption from social insurance contributions for all private entities, and exemption of corporate tax for entities with annual revenues of less than MNT 1.5 bn (EUR 5 m) (mining, oil, retail and tobacco sectors are excluded from the scheme);

- a monthly payment of MNT 200,000 (EUR 65) for three months to employees of private companies that keep their workers on the job despite declining revenues;

- a planned fuel subsidy to reduce retail fuel prices; and

- sector-specific measures for cashmere producers, including loans and stable prices.

In addition to this package, the Speaker of the Parliament announced additional measures aimed at ensuring financial and economic stability, preventing risks and making digital transition. This includes, among others, banking sector reforms towards more transparency and stability, an increase in foreign exchange reserve, the expansion of the activities of the credit guarantee fund and the further development of online education.

Outlook

According to first estimates by the IMF, the economy will contract by around 1% in 2020. However, a much deeper fall cannot be ruled out, as Mongolia’s growth prospects will largely be determined by developments elsewhere. Mineral exports are the main driver of growth, and they have been falling due to weak demand. Chinese imports from Mongolia fell by 25% during January-February, though the restarting of Chinese industries and coal imports could slightly cushion the effects of COVID going forward. The use of public funds will also need to be carefully administered by public agencies and accompanied by structural reforms to the legal environment for businesses. The impact on public finances will need to be assessed and measures to ensure post-COVID-19 fiscal consolidation could be needed.

Tajikistan

Economic overview

According to official government data, real GDP grew by 7.5% in 2019, supported by strong growth in manufacturing (14%), agriculture (7%) and retail (9%) (World Bank, 2020[10]). GDP per capita nevertheless remains the lowest in Central Asia. More broadly, growth continues to be driven by public investment, raw materials, and remittance-fuelled consumption, all of which render the economy vulnerable to deterioration in the external environment. Investment fell by 7% in 2019, with FDI inflows remaining concentrated in extractive sectors. Public investment has largely focussed on the Roghun hydroelectric power plant (RHP) (World Bank, 2019[5]). RHP investment derives from budgetary proceeds and risks crowding out much needed spending on healthcare and social protection, as well as reducing the financial space for longer-term reforms. The impact of COVID-19 will lower demand for key exports and demand for migrant labour, with falling trade and remittance revenues likely to strain public finances and investment capacity.

Economic impacts

Short-term indicators. The employment impact of the crisis might be very large, given the size of the informal sector and the return of labour migrants. In 2019, an estimated 500,000 Tajik migrants were working in Russia, generating remittance inflows equivalent to around one-third of GDP. By contrast, formal wage employment in the private sector within the country was estimated in 2017 at only 13% of total employment, leaving a large number of people vulnerable to the slowdown. The IMF expects the economy growth to fall to around 1% this year under its baseline scenario for the pandemic (IMF, 2020[10]). There are substantial downside risks if the health emergency lasts longer than expected.

Public finances. The country has high levels of external debt, estimated by the World Bank at 50-55% of GDP. The country’s export base is limited. Tajikistan’s budget may thus be severely affected by the economic and social costs of COVID-19. With the closure of the borders in Russia and return of migrants to Tajikistan, remittance inflows, estimated at USD 2.6 bn last year, are set to fall sharply.

Financial markets. The main risk factors are currency volatility and high dependence on imports (four times greater than exports). Falling remittances will undermine the country’s ability to pay for such imports. The official somoni-dollar rate has increased by 5% to 10.2 TJS, while a weakening rouble has reduced the value of those remittances still coming into the country. As a result, prices for staple goods have increased in the market, partly driven by panic buying.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. Tajikistan closed its borders and airspace for all international air carriers. Freight transport is still in operation, but foreign drivers are not allowed to enter the country. Kindergartens, schools and universities continue to operate. Public places including mosques, public transport and playgrounds are being disinfected on a daily basis. Awareness campaigns are being held to inform the population on the effects of the virus. Local containment measures are comparatively limited as of 14 April, with no prohibition of public gatherings and no lockdown. The World Bank has approved grant financing to help establish around 100 new, fully equipped Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds in health facilities across Tajikistan, and strengthen the health system’s capacity to treat individuals infected with COVID-19.

Monetary policy. The National Bank of Tajikistan raised its refinancing rate by 50 basis points, to 12.75%, in February, due to rising inflation. Annual inflation is projected at 9.3%. The required reserves ratio for savings and other liabilities has been reduced from 3% to 1% in national currency and from 9% to 5% in foreign currency until 31 December 2020.

Economic support measures. The government is implementing the Action Plan developed in 2018 to reduce the impact of external risks to the national economy. The Action Plan focuses on providing food security and price stability of staple goods, supporting vulnerable segments of the population, providing tax benefits and tax holidays to SMEs and postponing non-tax audits of businesses. Tajikistan has also created permanent headquarters for countering the spread of the virus and developed an Emergency Response Program, which mainly focuses on preventive measures, but also at reducing the negative consequences of the virus on the country’s economy. The programme is funded by IFIs. The programme is funded by IFIs. The IMF has approved immediate debt relief to the government and the EU will provide assistance of EUR 48million.

Outlook

The economic costs of the crisis will be high even if the country succeeds in keeping COVID-19 at bay, given the structural challenges facing the country, particularly its dependence on declining remittances. Over the short term, the government will need to focus on appropriate resource allocation to protect the health of the population, enforce containment measures, ensure food security, provide support to the private sector, including through financial programmes and tax reliefs. Over the long run, the country should continue its efforts to improve the business climate to increase private investment and employment.

Turkmenistan

Economic overview

According to the official data, real GDP grew by 6.3% in 2019, with growth continuing to be driven by the export of hydrocarbons. Trade turnover amounts to 117.9% GDP, with 90% of total exports being hydrocarbons, and over 80% of exports going to China. Turkmenistan is therefore particularly exposed to developments in that country. Early data suggests that the immediate impact of COVID-19 in China has already seriously affected Turkmenistan’s export revenues, with Chinese imports of Turkmen natural gas down 17% year-on-year in January and February 2020 (China General Administration of Customs, 2020[11]). Public revenues are being affected by the COVID-19 and falling export revenues and might impede further developments of the domestic economy, considering the large state presence in the economy and the relatively small contribution of the private sector to growth and employment (EBRD, 2019[12]).

Economic impacts

Short-term indicators. The IMF’s April 2020 World Economic Outlook projects growth of just 1.8% this year under its baseline scenario. (IMF, 2020[10]). Much will depend on the authorities’ success in keeping the disease at bay and on China’s recovery from the slowdown.

Public finances. Due to Turkmenistan’s dependence on gas exports, the country is particularly vulnerable to drops in demand in its major export markets, notably China. China has sought oil-indexed pricing agreements in its long-term gas contracts, which would imply a significant drop in the price of the Turkmenistan’s main export, and volumes have been reduced as well. This will limit the government’s ability to address immediate COVID-19 consequences and long-standing structural issues in the Turkmen economy will be further reduced.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. As of early April 2020, there were no officially confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Turkmenistan. The government has generally refrained from talking about the pandemic, and aside from some limited public health information, there has been little guidance to citizens or firms on preventive measures. Nevertheless, the government has taken a number of steps to prevent a COVID outbreak. It has closed its borders to non-nationals, and all non-Turkmen carriers have ceased flights to the country. Significant restrictions on internal movement have also been put in place. Turkmenistan has one of the highest ratios of out-of-pocket spending to total health expenditure in the world, which means that the costs of a major COVID outbreak might be passed onto an economically precarious population, particularly at a time when public finances are likely to come under severe pressure.

Monetary policy. Turkmenistan has an official fixed exchange rate of 3.51 manat/USD, which many observers have long considered to be seriously overvalued (the informal rate is close to 22/USD) and therefore deleterious to export-oriented enterprises. The effects of the COVID-19 may further reduce the competitiveness of domestic industries, while complicating trade and profit repatriation.

Economic support measures. As of early April 2020, the government had not issued any advice to entrepreneurs or outlined any plans on how the private sector would be supported should the COVID-19 pandemic have a serious impact on the economy. Restrictions on internal movement, however, had reportedly strained the supply of food and basic goods to shops and markets throughout the country, leading to prices increases and shortages. There have also been widespread reports of difficulties for citizens seeking to withdraw cash from banks and with card-based payments.

Outlook

In the short term, the government should prepare strong interventions to protect the health of its population and mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19. The primary driver of the country’s growth – natural resource extraction – has already been affected, and conditions are likely to deteriorate further due to falling global demand. In the absence of a robust and competitive private sector that might have provided alternative revenue streams, growth will fall markedly in 2020. Diversification efforts, improvements in the business climate and further opening to foreign investments are needed. Relaxing foreign exchange controls could also strengthen tradable competitiveness and investor confidence.

Uzbekistan

Economic overview

Real GDP growth accelerated slightly in 2019 to 5.6%, supported by a 34% year-on-year increase in investment, largely driven by direct lending to SOEs, and growth in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. Since 2016, growth has been supported by an active programme of economic reforms, including currency liberalisation. Despite these reforms, FDI inflows remain low, at 1.2% of GDP in 2018, though trends prior to the COVID-19 suggested that foreign investment had begun to increase. Uzbekistan has one of the more diversified export baskets in Central Asia and trades with a wider range of countries than most of its regional peers. Strong export growth and remittance contributions have contributed to a narrowing of the current account deficit from 7.1% in 2018 to 4.2% in 2019 (World Bank, 2020[10]). The government response to the COVID-19 will probably increase the account deficit, while growth of the domestic economy is likely to slow.

Economic impacts

Short-term indicators. No up-to-date information is currently available. Impacts might be very large, in particular due to the size of the informal sector. According to the Ministry of Labour, only 5.7 million people are employed in the formal sector out of 19 million in the labour force, leaving a large amount of people vulnerable to the slowdown. Growth for 2020 is expected to slow markedly, to 1.8%, assuming that the pandemic and required containment efforts peak in the second quarter for most countries and recede in the second half (IMF, 2020[10]).

Public finances. The government indicated that if export revenues decrease due to falling gas prices (following lower oil prices) and the devaluation of the Russian and Kazakh currencies, subsequent losses to the state budget (about USD 1.1 bn according to official figures) should be fully compensated by higher gold prices. However, the government has revised growth projections down from 5.5% to 3.7% for 2020.

Financial markets. Since the beginning of March, the UZS has depreciated by less than 1%, and the managed floating against the dollar has been maintained. The currency has been strongly supported by the Central Bank’s sale of foreign exchange which should increase by 30% compared to last year, on the back of higher gold prices.

Policy reactions

Public health measures. Uzbekistan declared a state of emergency on 16 March. Borders have been closed, and the capital, Tashkent, has been quarantined. All transport within the country has been put on hold, and schools, public places and non-essential businesses have been closed. Only freight transport has been excluded from bans.

Monetary policy. The Central Bank has decreased its policy rate by 1 percentage point mid-April to 15%, but the rate remains at a very high level to contain inflation amid external uncertainty due to the coronavirus outbreak and the expected effects of price liberalisation for selected goods and services. The bank also has offered several targeted refinancing operationsfor commercial banks (350 bn UZS), but did not change regulatory, capital or liquidity requirements.

Economic support measures. An Anti-Crisis Fund of UZS 10trn – EUR 950 m – (1.5% of GDP) has been set up to cover immediate medical and quarantine expenses, increase the number of social benefit recipients, provide liquidities, interest subsidies, loan repayment deferrals, guarantees to businesses, and finance infrastructure work in regions to sustain employment. The Fund also finances an allocation of UZS 200 bn (EUR 19 m) to the Public Works Fund to support employment and the construction of additional infrastructure, and of UZS 500 bn (EUR 47m) to the State Fund for Entrepreneurship Support to assist job creations by businesses. A series of additional fiscal measures have been introduced. In particular, tax deferrals for most affected SMEs and individual entrepreneurs until October; a moratorium on tax audits until the end of 2020 and on bankruptcy procedures until October; a deferral of the scheduled increase of tax rates; an extension of tax declaration submission until October; an ease of VAT calculation and payment requirements for small businesses; no excise tax and customs duties for the import of 20 types of basic consumer goods until the end of the year; and the suspension of rent payments for the use of state property by business entities that have been forced to suspend their activities. Finally, for households, parents are granted a 100% temporary disability benefit, and childcare benefits and material assistance are automatically extended for all beneficiaries.

Outlook

The global economic impacts of the COVID-19 weaken the Uzbek economy, notably through the fall of prices and sales of natural gas to Russia and China, the curtailing of remittances flows from workers in Russia (about 1.3 bn USD), the partial closing of Kazakhstan, the country’s main export market for fresh agricultural products, and the weight of announced relief measures on public finances. For the economy to withstand the shock, the government will have to strike the right balance between immediate measures to speed up the recovery and continued reform effort to sustain the country’s growth potential and the diversification of its economy.

Source: OECD.org. COVID-19 crisis response in Central Asia. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-crisis-response-in-central-asia-5305f172/

Notes

← 1. By contrast, China accounted for only about 17% of Uzbek exports in 2017, and this share has been falling steadily since 2013; the corresponding figure for Kyrgyzstan was 5.3%.

← 2. By mid-March, the NBK increased its policy rate from 9.25% to 12%, its highest since February 2017, and expanded the interest rate corridor to +/- 1.5%, from previous +/- 1%. This decision follows the prospect of increased pass-through inflation due to the depreciation of the tenge and the fall in oil exports (mainly to China and the EU) and prices.