GREEN OR BLACK TEA?

The Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline, more commonly known as TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) Pipeline, has come to Afghanistan, and as centuries of our people have done before, we prepare the tea and say “Khosh Amadin!”. While the TAPI project has seen considerable support from the Afghan government during the administrations of former President Hamid Karzai as well as the current National Unity Government (NUG), led by President Ashraf Ghani and CEO Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, the project has not been without dissent and opposition. This is particularly because of the inherent regional energy politics, summarized by Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid in the 1990s as “The New Great Game”, currently at play in Central Asia.

In many ways, the role of Afghanistan in the TAPI project represents the role we would inevitably serve which is to continue upon thousands of years of history as a hub and a central point for commerce and trade in the region. Rightfully, a project of this nature is not only expected but necessary in light of commonly heard phrases like “Rebuild Afghanistan” or “Afghan Reconstruction.” But, the prefix “Re” in both statements implies a return to something, a return to a time when Afghanistan was not synonymous with terrorism, civil war, foreign invasions, etc. Rather, TAPI, among many other such regionally focused infrastructure efforts, represents a return to the awe-inspiring tales of the caravanserais of the Silk Road, the hospitality of our local communities, the industriousness of merchants and traders and of course the pivotal role Afghanistan played in the growth of Central, South and Far East Asia. This article aims to dissect the Afghan incentives to participate in TAPI while considering the regional context and the interdependence TAPI creates amongst our neighbors.

TAPI 101

In order to assure we all have the basic facts, provided below for your convenience is a quick TAPI 101:

- TAPI is a natural gas pipeline being developed at the estimated cost of $10 Billion.

- The TAPI pipeline will be constructed alongside the Kandahar–Herat Highway in western Afghanistan, and then via Quetta and Multan in Pakistan. The final destination of the pipeline will be the Indian town of Fazilka, near the border between Pakistan and India.

- Design and construction is led by the Turkmenistan state owned “Turkmennebitgazgurlushyk”.

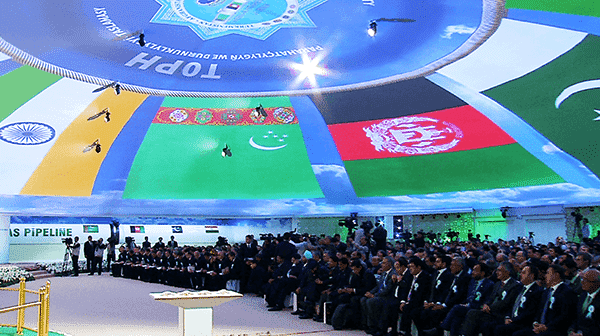

- Construction on the project started in Turkmenistan on December 13th, 2015.

- The pipeline is expected to be operational by 2019.

- Construction of the local segment began in Afghanistan on February 24th, 2018.

- The physical dimensions of the pipeline itself will be 1,420 millimetres (56 in) in diameter with a working pressure of 100 standard atmospheres (10,000 kPa).

- The pipeline will pass through 5 provinces (Herat, Farah, Nimroz, Helmand & Kandahar).

- Afghanistan will receive up to 5 billion cubic meters [bcm] (1.2 trillion cubic feet) of the 33 bcm to transit annually, along with transit fees totaling between $400M – $1B per year.

- This project is not to be confused with the Iran-Pakistan-India Pipeline (IPI).

On February 24th, 2018, at the welcoming ceremony in Herat, President Ashraf Ghani said that TAPI “… will help us fight poverty, unemployment, extremism and insecurity in our region… The policy of cooperation will ensure prosperity for our people, and economic prosperity is an important pillar of security and stability.

THE NEED FOR TAPI

“Why bother with the TAPI pipeline in the first place?” To answer that question, we have to look at each of the partner nation’s particular context.

TURKMENISTAN

Since the fall of the USSR in the late 1990s, Russia has been exploiting Turkmenistan’s immense natural gas wealth — up to 30 billion cubic meters per year — for its own profits. Between 2006 and 2008, Turkmen gas accounted for more than 70 percent of Russian Imports from Central Asia. Moscow purchased the gas at $130 per 1,000 cubic meters and was able to sell it to Europe for $354 per 1,000 cubic meters.

After more than two decades of this, Ashgabat is now looking to move away from Moscow and diversify its income sources. TAPI would allow it to do just that.

Thus it is no surprise that Russia initially bitterly opposed TAPI, as its interests remain in retaining a monopoly on pipeline routes through the Caspian states. However, in late 2010, Russia changed its TAPI policy and began advocating to be a part of the project, given their close relations with India and growing relations with Pakistan. Russia eventually engaged with the leaders of all four participating countries and in early 2011 secured support from former Afghan President Hamid Karzai, along with leaders of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan & Uzbekistan to participate in the consortium working to build the pipeline.

PAKISTAN

While that covers the supply side of the need for TAPI, the demand side is ever more pressing. Pakistan is among one of the most energy starved countries in the world while it has struggled to build a stable energy scenario and now it faces the worst energy crisis in its history. Its energy mix is highly imbalanced with natural gas comprising almost 48% of the primary energy supply. Crude oil, LPG and POL constitute 31%, nuclear and hydro are 11% and coal forms a small 8%. Because Pakistan is so highly dependent on gas, it constitutes 35% of its electricity generation. It is also estimated that Pakistan’s gas reserves are expected to be completely depleted by 2020.

As mentioned by various analysts, energy security in this day and age is a matter of national security. Hence, the Pakistani government must act decisively and effectively to meet their ever-growing energy needs, as a means of not just prosperity, but of survival. TAPI provides a stable and long-term means of energy supply as it would help meet 10% of Pakistan’s energy needs and 20% of its natural gas requirements per Pakistan’s Minister of State for Energy, Jam Kamal Khan.

INDIA

The situation is not too different for India. TAPI brings New Delhi much needed energy at a competitive price ($4/unit – almost half what it is used to paying). The imports from Turkmenistan alone will help India meet approximately 15% of its energy needs along with increased diversification and thus redundancy in energy resources. The inherent security risks of having the energy corridor run through Pakistan can be offset by economic gains to Pakistan in the form of taxes/fees for the pipeline transiting through the entire country.

This additional means of economic collaboration could help offset geopolitical pressures, namely Kashmir, as the financial interdependence would disincentivize other political issues from escalating. Crude oil is more expensive than natural gas, so by offsetting the price via TAPI, India stands to maintain its regional economic dominance. Given the initial success of the Air Corridor with Afghanistan, TAPI also allows opportunities to open trade routes with markets in other Central Asian countries.

POLITICS OF PETROL

Pepe Escobar refers to instability in the region as “the Liquid War” for the control of Eurasia. “Nothing in Eurasia is without an energy angle and it has all come down to the struggle for blue gold and black gold.”

HISTORY

Public opposition to TAPI is rooted mostly in the almost 30-year history of the project. Initially TAPI (as a project) was promoted by Argentina based Bridas Corporation, but the American company Unocal (later dissolved into Chevron), in partnership with Saudi oil company, Delta, sidelined Bridas’ by signing a separate agreement with Turkmenistan’s president Saparmurat Niyazov on October 21st 1995 to later form the consortium. The pipeline had to pass through Afghanistan, thus negotiations took place with the Taliban and since, then U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, Robert Oakley, had moved into CentGas in 1997, the project moved forward unobstructed. But, on August 7th, 1998, when American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam were bombed by alleged supporters of Osama bin Laden all pipeline negotiations were halted once Unocal withdrew from the consortium on December 8th, 1998. It was not until after the September 11th, 2001 attacks that a new deal on the pipeline was signed on December 27th, 2002 by the leaders of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan with strong US support as it would allow the Central Asian republics to export energy to Western markets without relying on Russian routes.

TALIBAN

Keeping in context Afghanistan’s reconstruction efforts, the US propounded the project as the ‘magic glue’ that will create a long-term interdependency among the regional players. This interconnectivity would in turn make the costs of conflict too high and the benefits of collaboration lucrative for all stakeholders. This point has been most recently affirmed by the Taliban spokesperson, Qari Mohammad Yusuf Ahmadi, whom in an email to media outlets, claimed credit for the project since it was initiated during the Taliban regime in Kabul, and promised that the group will ensure its security in areas under Taliban control. “The Islamic Emirate views this project as an important element of the country’s economic infrastructure and believes its proper implementation will benefit the Afghan people. We announce our cooperation in providing security for the project in areas under our control.”

Another Taliban statement followed by the breakaway faction, led by Mullah Mohammad Rasool, which also said it would support the project and prevent domestic and foreign groups from jeopardizing the prospects of its success. “We will not allow any group or state to disrupt this project.” The Taliban vow to cooperate and to not disrupt TAPI in areas under its control demonstrates that even they recognize; while war is optional, energy is necessary.

BENEFITS FOR AFGHANISTAN

To see such broad-based support for a project of this magnitude is quite inspiring, politics aside. The bulk of the value derived from TAPI is not just the direct gas supply and royalties, but also from a multitude of externalities that can be capitalized upon by the local, provincial and national populations.

TAP 500

Among the most far-reaching is the inclusion of the TAP 500 – also known as the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan Electricity Transmission Project — which will transmit 500 kV of power from Turkmenistan to Pakistan and will run alongside the TAPI gas pipeline. The additional transit fees earned by Afghanistan for this effort are expected to be around $50M per year. The powerline will run approximately 700 KM through the same five provinces. Thus the Western half of the country, which has suffered from severe electricity shortages to date, will benefit in the form of a new power supply source. This project will receive $150M in financial support along with technical assistance by the Asian Development Bank. This will translate into numerous opportunities to build the infrastructure, provide logistics support, security, consumables, etc. for the local communities in these areas. Raw materials provision as well as employment are just two relatively immediate impacts of TAP 500.

RAILROADS

The investment for the development of rail networks to support TAPI will see the completion of an incomplete legacy project which began more than 100 years ago as a competition between the Russian and the British empires.

When the Russians expanded their influence in Central Asia (then known as Turkestan), the British Empire saw it as a direct threat to their colony in India. Thus their proxy war for entry into Afghanistan — which could be used as a strategic base to invade either colonial India or Russian-sought Turkestan — began. In a form of infrastructural war, the Russians built railway tracks through Central Asia to the border of Afghanistan while the British built railway tracks through India to their respective border with Afghanistan. When World War II ended, the peace agreement signed between London and Moscow effectively brought an end to “The Great Game.” This left Afghanistan between two railway networks in the North and South, but lacked the infrastructure within its own borders.

Almost a century later, the current Afghan Railway Authority must reconcile between different railway gauge linkages used by Russians in Central Asia and the British India in today’s Pakistan; 1520 mm vs 1435 mm, respectively.

Now, with a strong push by various stakeholders the true economic impacts of an internationally connected railway system with domestic linkages and access can be experienced. The most important one is job creation as local Afghans will be needed to build, maintain and operate the railways. Transport of heavy materials and equipment will become less expensive and more efficient. Regional products and brands will have more national and international exposure alongside perishable foods which can be moved quicker and arrive in markets while still fresh. An increase in seafood consumption is a tertiary impact experienced by other nations. These benefits can continue to be enumerated and that does not include the residual value of the improvements to roadways and canals expected throughout the development of TAPI.

FIBRE OPTICS

Today, even the most remote provinces in Afghanistan utilize or desire digital connectivity. The investment in IT infrastructure and fibre-optic installation along the path of the TAPI pipeline will provide these communities greater access. Some complementary efforts such as Digital-CASA will also leverage regional resources and thus augment domestic connectivity. Faster and more broadly accessible internet could give a portion of the 35M+ population their first exposure to the Internet. An instant resource in education, data sharing, information democratization and ease of communication enjoyed by so many other nations could become commonplace throughout Afghanistan. As can be expected, numerous opportunities for technology focused start-ups will arise, while simultaneously there will be a mass migration of traditionally offline sectors online. Services such as education, banking, health services, travel agents, tax accounting, language translation, phone operators, job seeking and 3D printing are all examples of industries that are typically disrupted by the introduction of digital technology as they can all be easily brought online to eliminate obstacles posed by distance and the ever-challenging mountainous landscape of Afghanistan.

ENERGY ACCESS

Among the immediate values to the Afghan nation is a lesser known secondary outcome of the TAPI pipeline which is the equitable distribution of clean-burning, environmentally friendly and cost-effective household gas. As part of the project, there will be investments made to distribute the allocated portion of gas to residential communities along the path of the pipeline. Thus, providing warmth and cooking facilities, basic needs which have, to date, lacked in most of the provincial areas of Afghanistan and specifically in the western provinces. Yet again, this is an opportunity for industrious Afghans to participate in commercial construction, maintenance and local installation services. Typically, copper tubing, aluminum alloy tubing, or steel tubing is used to reach “the last mile” in residential contexts, thus there is an additional opportunity for smelting facilities, importers and the overall mining sector to add value and retain some rather lengthy relationships with the TAPI project as well as local gas resource providers.

While one of the initial priorities of TAPI is that it will serve as a source of power and energy for industries, establishment of gas-based medium capacity power plants and gas-consuming industries will be productive investments all the way to the residential level. Such power plants and grids will provide solid investment opportunities for domestic and international manufacturers and provide small industries the chance to grow and create needed jobs.

AFGHAN HOSPITALITY

The true success and thus value of the TAPI gas pipeline through Afghanistan’s five provinces should not be measured by the signing of bilateral agreements or even the construction progress of the physical pipeline, itself. The true worth of this project will be felt in terms of the eventual secondary and tertiary sectorial influence a project of this scale will inevitably have throughout the country and the region.

As with all aspects of the development of Afghanistan, this will not be a success accomplished by the government, the international community or even our regional partners. Rather, the commitment by the community of Afghans at home and abroad to support such efforts, which as we stated at the onset, are inevitable, will be the determining factor in TAPI’s success. Afghanistan’s people, organizations and government must unify, in general, and specifically around the TAPI pipeline in order to realize the vast opportunities that this project presents. From the provincial heads of state to the local artisan, the TAPI pipeline project has the capacity to transform lifestyles in the communities through which it will run. The responsibility falls on each individual Afghan to recognize those opportunities and work for the greater good of our people. As we do in every home, office and public arena, we must maintain our internationally famous Afghan hospitality and say to the TAPI project, “Khosh Amadin!” so the work can begin!

Photos: (AOP, Dynamic Vision)