Lean Thinking: Starting A Business From Zero

Akbar* has an idea for a food service that makes and delivers lunches to office staff.* The concept is simple: provide wholesome, hot lunches, delivered to offices at affordable prices. Akbar discovered that staff of small and medium-sized offices spend around 100-150 Afghani daily on lunch. By focusing on plazas with large numbers of businesses and employees, he figures he can provide lunches for around 80 Afghani per person. Akbar’s problem is he has very little by way of capital. Akbar currently works in food preparation at a restaurant on a low salary. So far, he hasn’t gotten a lot of help from the friends and investors he has approached.

While some businesses require a significant investment early on, many entrepreneurs find it’s smarter to test their ideas through micro-experiments that help them hone in on real costs, real opportunities, and real customer needs. In high-risk conflict zones like Afghanistan, the flexible, minimal cost approaches of “lean” entrepreneurship can be especially appropriate.

In light of the increased interest of youth in Afghanistan to start their own business, following are some principles for putting your small business idea on the lean diet.

*Akbar’s story and business are fictional, but based on real situations and illustrate the principles of lean start-up.

1- Self-fund in the beginning

Investors typically want to see more than a creative idea and a thorough plan. Proven results are what will encourage them to help you scale up your business. If you think you’ve got a profitable idea, put your own resources to work first and get those initial results. Entrepreneurs who start a business with their own resources will be more inclined to delay expenses that may not be necessary in the start-up phase, such as an expensive accounting system or fancy office. Business people who self-fund generally benefit from greater personal dedication and a greater sense of fulfillment as they create value with their own resources and the “sweat equity” of their own energy.

Rather than quitting his job, Akbar went part-time so that he could continue to pay for his expenses while he worked at getting the business off the ground. He cut out certain expenses to accommodate a reduced income. He sold his motorcycle to his cousin to free up some start-up cash, but with the understanding that he could still use it occasionally to further his research and marketing.

2- Get Customers to Pay for Products or Services in Advance

When Halima introduced her design for locally made school uniforms to the administration of private schools, she was met with enthusiastic response and several verbal agreements. If she could manufacture uniforms at the quoted costs, they promised they would buy. Halima imported machinery, rented factory space, hired a small army of tailors and got to work. But once the product was ready, the schools didn’t deliver on their promise. Halima was stuck with an inventory she couldn’t move and a family debt she couldn’t repay.

“Let an early version of your product serve as a research tool, and be willing to iterate (make small, rapid changes in direction) as you learn what real customers really want.”

It’s easy for customers to say yes to a theoretical offer, but until they put money down, the real value they place on a product or service is unproven. Businesspeople can make upfront payments attractive to customers by discounting invoices: for example, offering 20% off a service if the client pays for a month, quarter, or year in advance. Crowd-funding is built on the model of advance-payment. Crowd-funding campaigns preoffer customers benefits before a business is launched, which gives both the entrepreneur and his investors assurance that an idea is workable before the first dollar is committed.

The reverse of this concept is supplier credit. Start-ups can work with suppliers to delay payment on equipment or materials. The goal is to create a cash flow advantage by speeding receipts and delaying payments where possible. Akbar set a target of 100 initial customers willing to pay half of the first month’s fee in advance. He was honest with his first customers about his cash flow needs and discovered that several were happy to pay upfront. He also negotiated with a supplier to give him bulk foods in advance to be paid off as he spent them.

3- Start with a Minimum Viable Product and Adapt as You Go

Full products or services take time and money to build, and the risk is building something that no one needs or is willing to pay for. There may be a minimal version of your product that you can test on the marketplace first. If you’re selling a new beauty product, try one, rather than several lines, start with simple packaging, and retail in existing stores on consignment. If you’re building a technological solution get an early version of your product out in the market and listen to the feedback you get. Perhaps the worst mistake a businessperson can make is to get attached to her product too early, before it has proven itself in the market, a phenomenon sometimes called “product blindness”. Let an early version of your product serve as a research tool, and be willing to iterate (make small, rapid changes in direction) as you learn what real customers really want.

Akbar thought about his irreducible minimum. He needed a kitchen and a delivery mechanism, but they didn’t have to be his own. Akbar contracted with his restaurant to use their facilities which became a win for both businesses. He arranged for a third-party service to manage deliveries, something they were able to do inexpensively along with their other activities.

“The lean mindset can help businesses get going sooner, smarter, and better equipped to respond to changes and discoveries.”

4- Make Your First Business Plan an Adaptable Learning Tool

Many of the business plans taught in business schools are too long and too specific to be practical for startups. They can give an entrepreneur a false sense of assurance that all the answers have been found when in fact they may not even be asking the right questions. Start with a simple, 1-3-page plan that answers the important questions: What problem am I solving? Who are my customers? How will I find them? How will I make money? Let your first set of “answers” be hypotheses to be tested rather than fixed conclusions. Your plan should be a living document that you adapt regularly as you test your idea.

Akbar’s initial idea was a menu of lunches from which customers could select. He soon found this was too complicated and not all that valuable to the customer. He settled on a fixed five-day plan. He also discovered that most of his clients were willing to pay a little more per day (120 Afghanis), but preferred meat daily, rather than twice a week. His flexibly-written plan allowed for market research to be an ongoing cycle of rapid experimentation and adjustment.

Illustrations by: Diba Qasemi

Illustrations by: Diba Qasemi5- Enlist the Help of Your Community

Nearly all these ideas depend on a mindset of “open collaboration”, and that is perhaps the main principle of effective lean start-up. Gary, a business consultant who has observed and assisted Afghan startups for more than a decade finds that success in a new enterprise often depends on how much the founders positively involve their community. Gary observes, “those who incorporate a commitment and accountability to community within their business plan both benefit from the investment of the community and give a great return on investment to the same community.”

Businesspeople are often reserved in involving their network because of pride or fear of having their ideas or resources stolen by others. But when businesspeople collaborate freely with one another and with stakeholders in their community, they increase their pool of resources and specialists, improve their ideas, and get greater buy-in from potential customers. In the end, money is not the only, or even the main investment a new business needs. The lean entrepreneur understands this and partners widely with people in his community to gain these valuable non-financial resources.

In contexts of limited resource, high risk, and rapid development, the lean mindset can help businesses get going sooner, smarter, and better equipped to respond to changes and discoveries. In addition, lean start-up models can make running a business accessible to people who don’t have extra money. That means more talent and creativity put to work to solve problems and add value in the emerging Afghan economy.

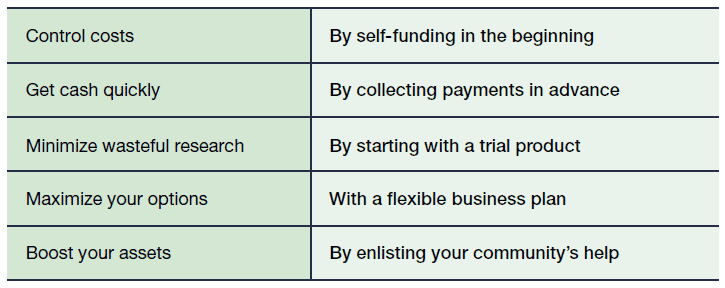

Create a Lean Advantage