How Roeen Rahmani is Nurturing the Next Generation of Afghan Leaders

From graduating high school at the mere age of fourteen, to launching Afghanistan’s first private university, to consistently advocating for investment in quality primary, secondary and higher education – the impact of Roeen’s journey can be seen through the many facets of Kardan University, Kardan International School (KIS) and Kardan Schools, the country’s most prestigious and innovative private education group

“Educational reform must become a national priority. By investing in the education of our children and youth, we can usher in a new era of prosperity and self-reliance in Afghanistan. Our future generations deserve better.”

With a smile evident through his voice’s lightness, Roeen explains “I would have graduated from high school at 13 had it not been for my family’s migration from Kabul to Peshawar.” Roeen’s sense of humor and intuitive intelligence is complemented by a refreshing dose of realism and resolve – a rare culmination of qualities that have allowed for Kardan to become the trailblazing institution it is known for today.

Born in Kabul in 1982, Roeen and his four siblings have all gone on to attain impressive levels of achievement, often in the line of public service and social impact. For the Rahmani family, education was the cornerstone of their upbringing: “my siblings and I had a library of 900 books at home. Any money that came into our hands went directly to growing the library. There wasn’t a book on those shelves that went untouched – I’m sure we read all 900 titles!”

In 1992, Roeen and his family fled to Pakistan, with little idea of what life awaited them there. Books, learning, and a thirst for knowledge offered a safe haven, and he attributes those years to have had a major impact on his attitude and focus today. “I was reading anything I could get my hands on. Consciously and not, those books have deeply impacted how I see the world, and who I have become today.” When asked what his favorite book is? “You can never choose between your best friends! It’s the same with books. I could never choose a single title above all.”

A self-proclaimed introvert in his early years, Roeen was fascinated with learning how things ‘tick’. It wasn’t unusual to find him taking things apart and rebuilding them with any objects he could lay his hands on. Nevertheless, as the Rahmanis put down roots in Peshawar, education above all else dominated family’s values. Strict punishment was administered if the children brought home less than optimal grades.

Keen to explore new horizons, Roeen signed up for a one-year computer science program in Peshawar at age 15, with no idea of how a computer even worked. “I had missed the first 20 days of the classes and was completely computer-illiterate. On my first day, when the instructor asked us to turn off our computers, I struggled to find an ‘off’ button. I remember a classmate reminding me that it was a computer, not a television. In two months, I ended up top of my class.”

Sometimes manifesting as playful naughtiness, Roeen’s insatiable appetite for curiosity led to him being expelled from his computer science program after hacking into the school’s IT system. “I was just curious if it was even possible to break into – the dean thankfully took it as a sign that I was ready to graduate. Even though I was expelled, I still received my diploma.” Chuckling to himself, Roeen informs us that in spite of the incident, he is still invited to the college to speak at orientation events, though he always discourages incoming students from ‘hacking’ as a hobby!

At age 16, Roeen enrolled at Preston University in Peshawar, Pakistan, intending to continue his studies in computer science. “It was actually my academic advisor who would ultimately change the course of my life by suggesting I pursue a degree in business instead.”

Once he began studying business administration, Roeen became utterly immersed in the realm of management and mathematics, relegating computer science to the backburner. “I loved learning about the world of business so much that I forgot all about computer science, though I am still incredibly grateful that I got that basic knowledge early on.” Roeen would then go on to achieve three MA degrees, all under the age of 30. Two at Preston University, first in finance, then in project management. His third Master’s was an MBA awarded by the Schulich Business School of York University, one of Canada’s most selective and prestigious business schools.

In late 2001, Roeen returned to Kabul to work for an NGO. His position there as program director left him acutely aware of the scope of the task ahead in rebuilding Afghanistan’s collapsed institutions, and hungry to be part of that important change. And so came about the idea of Kardan. “I was drafting the idea of Kardan and pitching it constantly to the NGO’s Director as a potential program. She loved the concept, but submitted it as a proposal to be funded by a donor – something I did not agree with. The NGO focused on short-term programs and I knew Kardan would be a very long-term endeavor.”

Roeen pitched the idea of Kardan to a close group of five friends, amongst whom the foundations of the institution’s future would eventually be laid. Recalling the story of an accountant at the NGO where Roeen then worked, he noted just how much of the national workforce then occupying key positions had little to no technical knowledge of their work. “He was an accountant because we could trust him. He was a trustworthy and hard-working man, but I knew he struggled greatly with the lack of foundational knowledge he needed for that role. With Kardan, we wanted to fill that gap.”

“Access to education in this country should be universal, but that doesn’t mean the education quality should be substandard. We need to hold education providers to account for delivering the high standards needed for everyone to be able to benefit from a quality education.”

On a bitterly cold morning in February 2002, Roeen and his friends-turned-partners launched a 3-month training program in rented premises, focusing on the basics of management, accounting, communications, and marketing. Four of these five founding partners would be working as instructors, with Roeen managing all else. For Roeen, managing a school was ‘on the cards’ from an early age. “When I was a kid, I always wanted to run a university. I’m not sure why that was, but it was constantly in the back of my mind, and I never wanted to do anything else. I just wanted to manage schools.”

Roeen vividly recalls Kardan’s first classroom. “We had worked for weeks to develop and market our programs to get students to sign up. It was a Saturday that I’ll never forget. When I entered our classroom, I was shocked to find that it was totally empty – not a single student present! No one had joined our training program. How could this be possible?”

The disappointment of that first day came as a sobering dose of reality for Roeen, and an early test of his levels of perseverance. “It was easy to blame everyone else for that initial failure; the education system, the empty promises of potential students to join, the country’s situation, etc. Us five partners all had jobs to go back to. But, standing outside that classroom, I made a decision to persevere, and that resulted in the Kardan you know of today.”

The following Saturday, after a week in which the founding five worked tirelessly at recruiting students, Roeen arrived in a classroom of 11 students – all immersed in learning. One such student commuted from Paghman, leaving home at 4:30 am to reach the Shahr-e-Naw institute for a 6:30 am class. Such displays of dedication have consistently remained the case among Kardan students, reflected also by the long-established waiting lists associated with Kardan institutions.

A natural-born entrepreneur, Roeen has both been training his eye to spot market gaps from an early age, as well as familiarizing himself with the hardships so often accompanying risk-taking. At only 15, Roeen opened a computer hardware and components store in Peshawar, Pakistan. “It was an uncertain time. I opened the store when no one was really interested in buying those things. It was a disaster and a very tough six months. I had to walk countless kilometers between the store and our home because I couldn’t even afford the bus fare.” In retrospect, these early experiences of the unsuccessful computer store in Peshawar, and the struggles Kardan Institute faced in its infancy, proved to be fertile learning opportunities for informing the bold, shrewd and determined attitude Roeen needed to cultivate in order to successfully launch – and sustain – a venture such as today’s Kardan.

Launching with only 11 students, Kardan Institute initially offered short-term certificated business and accounting programs. Interest soon grew, and with the first cohort’s graduation came the need to swiftly expand and scale up operations. The second cohort of 50 students would meet for classes in a three-bedroom apartment in Shahr-e Naw, with the third cohort meeting in an even larger building. “We started adding classrooms every other month, to the point that there was no more space available for extra classes. There was no BusinessDNA at the time as a medium to reach out to potential students, it was all word of mouth. Within just three years, Kardan’s reach extended outside of Kabul, with students in other provinces consistently demanding that we open campuses across the country.”

From the outset, Roeen was insistent that any profit made through Kardan should be immediately reinvested. He would patiently repeat to Kardan’s founding partners that the Kardan project would never be motivated by profit-making. Nevertheless, Kardan’s exclusive focus on providing short-term professional training programs would come under pressure with the 2005 revision of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, allowing for the emergence of private universities. Recalling the fear of countless new private universities flooding the country as the precursor to how Kardan University came into existence, Roeen recounts “I knew that after a few years, we wouldn’t be in much demand because the gap would be filled by these private universities and there would be no need for our programs. It was an interesting feeling, like a reaction to losing something dear to me. I couldn’t imagine not working at Kardan and not being in a classroom setting.”

With the constitution now allowing private universities to form, Roeen set out to meet with officials at the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) and transition Kardan’s short-term programs into a university. Roeen would visit the Ministry from nine am to five pm, every day, for countless months. At times, the guards wouldn’t search or stop him because they thought he was an employee of the Ministry. “I would be lucky if I got one meeting a week. I looked so young and thin that they never took me seriously [chuckles]. But I am very persistent. I never give up until I get a satisfying answer.” At the MoHE, Roeen’s nickname became “bacha-gak”, (the kid), and as his persistence became relentless, so it morphed into “bacha-gak-e-Shala” (the persistent kid).

Roeen’s aspirational vision for Kardan is matched with tangible and measurable outputs. Kardan’s Impact Report 2014 – 2018, a performance metric for the university, indicates an impressive 4,250 million AFN – $55m – cumulative contribution to the Afghan economy through the university’s and students’ expenditures, between years 2014 – 2018. According to the report, Kardan’s employment rate for graduates of both bachelor’s and master’s programs stands at 88%, a staggeringly high figure given the national unemployment rates. The Impact Report is part of Roeen’s mission to sustain and ensure Kardan is consistently pushing for growth and innovation. “It is one thing to start something but another to sustain it. It requires unwavering passion and purpose. It’s like going to the gym. You pay the fee, and you go once, but it needs the persistence to get the right results.”

“It is one thing to start something but another to sustain it. It requires unwavering passion and purpose.”

Roeen’s frustrations with Afghanistan’s educational, vocational and institutional regulations are the result of countless years of bureaucratic limbo and unclear guidelines, an indication of how entrenched and overdue the areas are for reform. “Unfortunately, our education system is very flawed. The policies are typically written by those with limited experience. Access to education in this country should be universal, but that doesn’t mean the education quality should be substandard. We need to hold education providers to account for delivering the high standards needed for everyone to be able to benefit from a quality education.” Roeen believes that Afghanistan must maintain an effective strategy in investing in education and training for the future. Referring to the ‘value’ of a higher education degree in Afghanistan, he makes the case that the relevant ministries of education have not yet shown that technical and vocational training is of any real benefit to students, with them generally regarded as training for ‘low-grade jobs’.

With over 1,800 applications for financial aid, and over 1,100 of them approved and supported throughout the students’ educational journey since 2002, Roeen puts Kardan’s ‘money where its mouth is’. Whether it is a global pandemic or the realities of a fragile country, he is committed to ensuring that Kardan eliminates as many obstacles as possible, impeding young Afghans from accessing quality education opportunities. “I was definitely born to serve. I even love picking up the broom and cleaning the classrooms. When we began marketing for Kardan University, I would take a ladder and put up the posters myself. Nowadays, when I move around the city and see Kardan’s logo everywhere, I feel so proud and humbled that I can’t even explain it in words.”

When visiting any of Kardan’s institutions, their mission statement is evident at a glance – ‘A vibrant university inspiring academic and professional excellence’ – a clear indication of the leadership’s focus on Kardan students and how they are shaped into Afghanistan’s future leaders and problem-solvers. “We need solid structures in place to ensure that what is being taught today will be solving the problems of tomorrow.”

“We need solid structures in place to ensure that what is being taught today will be solving the problems of tomorrow.”

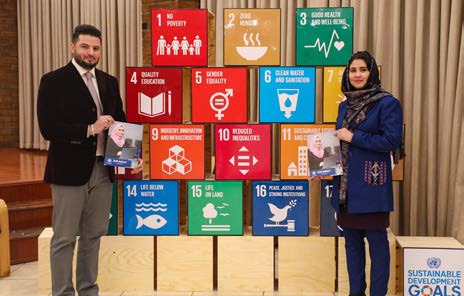

Mursal Akhtari, a 3rd-year business administration student at Kardan, is a perfect example of the types of students that Kardan attracts. “Before joining Kardan, my purpose was to study business administration someplace that could help me with my business idea. After studying two semesters at the Kardan University and getting to know some of the well-known Afghan entrepreneurs through Kardan’s business seminars organized by the career center, I got my license and launched my own business.” Over 600 Kardan graduates have gone on to become Fulbright, Chevening, DAAD, and other prestigious graduate studies scholars, far more than any other higher educational institution in the country.

Since transitioning into a university, Kardan now boasts an impressive alumni community of over 30,000 students. Abdul Wakeel Hamidi, a 2018 Kardan graduate and current Advisor to the Minister of Urban Development and Land, believes that the Kardan community is why its students are so dedicated and proud to be Kardanians. “At Kardan, from the guards to the President, all treat students well and with respect. Most universities do not listen to the students’ proposals and feelings, but at Kardan, everything is student-centric. They take action and set policies based on students’ advice.”

Although Kardan’s founding partners have now all gone their separate ways, Roeen’s inner circle includes staff who have been with the university for over a decade. The Chief Operating Officer, Mirwais Nahzat, has been friends with Roeen since 1995, attending high school in Pakistan together and now working steadfastly by Roeen’s side. “I am still at Kardan because of its commitment to promoting knowledge and inspiring the next generation of Afghan leaders. The university is indeed a microcosm of educational transformation – one mind at a time. The secret to Kardan’s success lies in its focus solely on education and a commitment to fundamentally transforming the education sector of Afghanistan.”

Roeen consistently refers to Kardan’s foundational success being largely due to the commitment and unmatched leadership of Kardan’s Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs, Mrs. Meena Rahmani – Roeen’s wife. Testament to her impact on Kardan, is her leadership of the university’s MBA program, which currently stands as one of the best business programs in Afghanistan. “She’s a natural leader. She believes in driving local talent and unleashing the true potential of our students. She feels an immense responsibility to everyone at Kardan, her community, and the entire country.”

“I am still at Kardan because of its commitment to promoting knowledge and inspiring the next generation of Afghan leaders. The university is indeed a microcosm of educational transformation – one mind at a time.”

– Kardan’s Chief Operating Officer,

Mirwais Nahzat

Mrs. Rahmani’s sentiments regarding Roeen are echoed on a similar wavelength – an indication of the teamwork and devotion behind-the-scenes at Kardan. “Roeen’s journey of transforming a small investment into the country’s leading institution is full of ups and downs and day-to-day challenges, but his agile and forward-thinking leadership never allows him to stand still. You talk to him every day, and you will find positive energy in his thinking, and this is what he has been transforming to his teams, making Kardan a vibrant home for hundreds of forward-thinkers.”

Roeen sees passion and purpose in learning among his students. On a bitterly cold evening in January 2007, he closed Kardan for the day, turned off the school’s generator, and set off to drive home to Macroyan. When he reached Haji Yaqoob Square in Shahr-e-Naw, he witnessed something that continues to be one of the most inspiring moments of his life. “Due to the power shortages, it was rare to have electricity in the evenings. It was at Haji Yaqoob Square that I saw three of my students huddled together on that freezing night under the only working street lamp in the city. They were using that one lamp to study.”

In addition to the university, Kardan has three kindergarten-to-twelfth grade schools in Kabul, with over 2,000 students, including Kardan International School (KIS) – Afghanistan’s first digital school. The digital curriculum at KIS is supplied by McGraw Hill, a Californian education body, for which all teachers received extensive training led by international education experts. Roeen’s aim for Kardan is on the entire arc of education, for students of all ages desiring to engage in lifelong learning. In the case of KIS, this commitment is elevated to a whole new level. Explaining the rationale behind it, Roeen tells us that the “long-term prosperity of our future generations depends on our willingness to embrace relentless and expanded digital transformation.”

As our conversation with Roeen was coming to an end, we brought up the story of a ten-year-old student at Kardan International School who had hacked into the school’s Wi-Fi. “I definitely know that student,” Roeen laughed. “At Kardan, we will never expel a student for their curiosity – as I was back in the day. We just want to give them quality education and challenge them to hack us again and help us become stronger.”

Despite the challenges presented by Afghanistan’s outdated education model, Roeen is upbeat about the prospects of higher education serving as the engine of growth that will propel Afghanistan on its journey forwards. He believes that higher education in Afghanistan should be the top development priority in the country. Despite the sector’s significance for Afghanistan’s developmental prospects, according to Roeen, higher education has received very limited attention and resources, inhibiting its ability to grow and respond to overwhelming demand from the country’s burgeoning youth population. 70% of the Afghan population is under 25 years of age(2), indicating the sheer level of demand for quality education, and human capital development for job and opportunities creation. Commenting on the global pandemic, Roeen is concerned that it will have further compounded existing inequalities in Afghanistan’s higher education sector: “as it stands, with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, higher education in the country is virtually stalled, notwithstanding the ingenuity of a limited number of universities in Kabul city”, says Roeen.

“We’re working closely with the next generation of Afghans at Kardan. We can feel their thirst and energy for education. Afghan youths have all the ingredients required for a successful career: ambition, passion, and the drive to do well.” According to Roeen, in order to advance a development agenda in the higher education sector in Afghanistan, imaginative and market-led sustainable approaches are needed, with strategies that are based on generating the most value from public and private spending on higher education.

“Educational reform must become a national priority. By investing in the education of our children and youth, we can usher in a new era of prosperity and self-reliance in Afghanistan. Our future generations deserve better.”, Roeen ended.

As specified by Kardan’s Chief Strategy Officer, Rohullah Rahimi, the top five focus areas to advance higher education in Afghanistan include:

- Regulatory reform should be at the top of the development agenda. We need a lean but effective public regulatory environment to uphold standards. We should abandon sprawling bureaucracies in favor of empowering universities.

- Supportive student loan services should be introduced to enhance student economic wellbeing, and infuse enhanced student-led spending in the higher education sector. The government should step in and take a leadership role here.

- Systems development within the Ministry of Higher Education, focused on reducing redundancies, restructuring for sustainable innovation, and encouraging competition, are all desperately required.

- University entrance examinations should be reformed. Kankor examinations are increasingly irrelevant. We should move towards testing and certification models similar to the one at the regional and global levels.

- Enhance technology integration in content and delivery of education services to allow Afghan students and institutions of higher education to experience the ‘leap effect’ that can be leveraged by access to technology.

“We’re working closely with the next generation of Afghans at Kardan. We can feel their thirst and energy for education. Afghan youths have all the ingredients required for a successful career: ambition, passion and the drive to do well”