Kick-Starting the Afghan Economy

5 Recommendations to Foster Entrepreneurship in Afghanistan

On October 5, 2016, the Government of Afghanistan presented the Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework (ANDPF) in Brussels to representatives of the international community. The ANDPF is the country’s five-year plan for the years 2017 to 2021 and lays out the vision “to achieve self-reliance, increase the welfare of the Afghan people and build a broad-based economy that creates jobs.” Particular emphasis has been put on self-sufficiency, which is a highly laudable aim that represents a step-change from the past. And indeed, the government has made great strides thus far: domestic revenue collection has increased by

15% in the year 2016, exceeding the budget target by around 5 per cent, according to the World Bank. The same institution projects the economy to grow by 2.6 per cent in 2017, a significantly higher rate than the 1.3 and 1.1 per cent growth rates of the years 2014 and 2015, respectively.

So, is Afghanistan on track to meet its ambitious objectives? Unfortunately, the answer is no. With an average annual population growth rate of 3 per cent and an estimated 400,000 Afghans entering the labor market each year, GDP growth remains significantly below the 8 per cent required to fully employ Afghanistan’s growing labor force and increase revenue collection further.

SMEs are the engine of jobs growth and development

Industry experts, researchers and government officials increasingly highlight the role that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play in creating employment and income. Because of their agile structure, SMEs quickly adapt to changes in the economy, technology and consumer behavior. Hence, SMEs are the cornerstone of policymaking for new ventures and job creation.

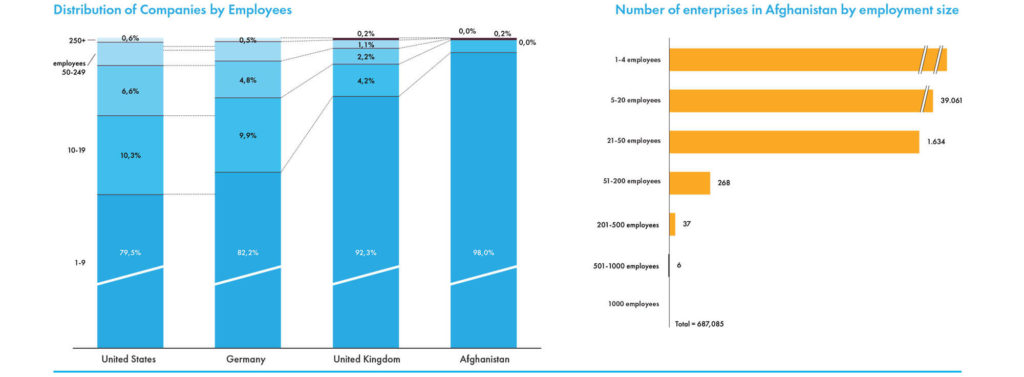

According to the Central Statistics Office of Afghanistan, more than 98% of all firms in Afghanistan have less than 10 employees, a further 1.7% of all firms have 10-19 employees. Only 0.2% of all firms in Afghanistan have 20-49 employees and the remaining 0.1% have more than 50 employees.

SMEs are nimble and flexible. However, they have several disadvantages and as a result, cannot benefit from economies of scale and face other impeding factors that are exacerbated in Afghanistan. These drawbacks can be considered the root cause of start-up failures. According to the OECD, most start-ups fail within the first five years of their establishment, varying from 63% in the UK to about 47% in The Netherlands. Given that start-up failure rates are generally at about 50%,

“a steady and ever-increasing flow of new ventures is needed to increase the number of SMEs in Afghanistan.”

Unfortunately, new firm registrations have decreased in the past years and stand at more than 50% below their level recorded in 2012. It is therefore of paramount importance to ensure a steady and increasing flow of new business registrations. Unfortunately, new firm registrations in Afghanistan have continuously decreased in the past years and remain at more than 50% below their level recorded in 2012, illustrating the hesitance in launching new businesses and highlighting a sluggish business sentiment in the country.

A well-functioning SME ecosystem can kick-start the economy

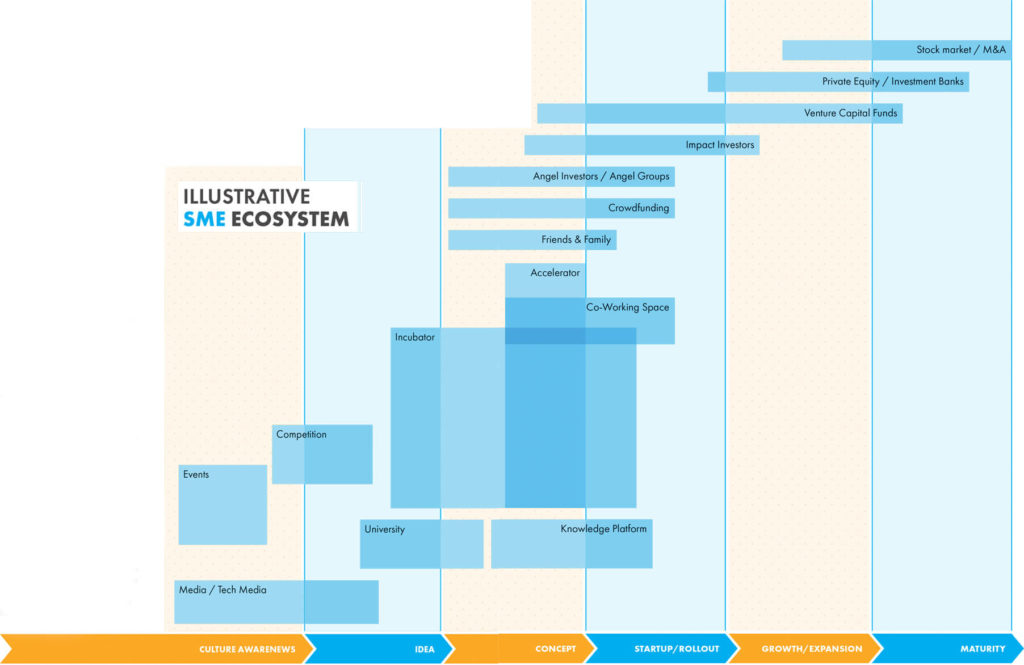

In order to promote viable businesses and support sustainable firm creation, Afghanistan needs to lay the foundation for a business conducive SME ecosystem and strengthen supporting institutions and organizations. A more institutionalized approach to strengthening SMEs in Afghanistan will support firms in all life stages, increase firm survival rates and facilitate high-growth firms to prosper by meeting endogenous demand and capitalizing on growth opportunities.

Ecosystems are formed by people, enterprises and various types of organizations interacting as a system to facilitate education, training, know-how, networking and funding in all life stages of a firm. The SME ecosystem impacts the ease and speed at which entrepreneurs and SME owners can establish new ventures and scale them into sustainable and competitive businesses.

“The Afghan government as well as the private sector have pursued several initiatives to strengthen the environment for new and existing firms. However, more needs to be done for the nascent ecosystem to thrive.”

In his landmark book, Startup Communities, Brad Feld posited that it takes about 15-20 years for a vibrant SME ecosystem to develop in a city or region. Building on prior efforts, Lebanon, a post-conflict country that has emerged after years of civil war, implemented innovative and aggressive policies in the 2000s to spur the growth of their startup ecosystems and is now considered the most thriving startup hub in the Middle East, apart from Tel Aviv.

Recommendation #1

Promote a culture of entrepreneurship

Few Afghan youngsters aspire to become an entrepreneur. When asked, most children and students want to become a doctor or an engineer because these professions hold prestige and social acclaim. However, entrepreneurship receives little media or public attention. Therefore, a dedicated campaign is needed – through documentaries and interviews – to raise awareness about, create excitement for, and celebrate successful Afghan entrepreneurs.

The Afghanistan Business Summit (ABS) is an example of an annual gathering of Afghan entrepreneurs, celebrating successes and sharing insights, ideas and resources. But it’s a small drop in an ocean and so much more needs to be done to promote entrepreneurship.

Recommendation #2

Provide a single platform to conglomerate all available programs and information

Information on entrepreneurial programs and initiatives in Afghanistan is scattered and dependent on personal contacts and networks, inhibiting meritocracy and entrepreneurial drive. A single platform providing information and guidance on available grants, upcoming competitions, incubator/accelerator programs, technology parks and initiatives as well as venture capital and public funding programs would help divulge Afghanistan’s advantages for startups.

Recommendation #3

Set-up a one-stop-shop for new ventures and provide a tax holiday of five years to spur new venture creation

Given the ever-decreasing number of new firm registrations in Afghanistan, a dedicated push to incentivize new venture creation is much needed. A one-stop-shop, offering a multitude of services, ranging from simplifying firm registration to providing one-to-one information on the myriad of funding and financing support programs could assist the would-be entrepreneur. “To create the much-needed impetus for Afghanistan to spur new ventures, the government should introduce a temporary five-year tax holiday for new firms.”

Recommendation #4

Adapt business, legal and regulatory requirements to meet the prerequisites of the international investment community

Afghanistan’s private sector needs to diversify funding sources and become less dependent on international aid. The growing impact investment community offers the opportunity to link Afghanistan to regional and global investors. Meeting the prerequisites of the international investment community will help infuse know-how, leverage networks and mitigate donor dependency.

However, international investors are used to international standards of deal-making and expect support when it comes to enforcing shareholders’ rights. The shareholders’ agreement is at the heart of any partnership amongst shareholders of a company. The agreement usually regulates ownership and voting rights, defines control and management of the company, and makes provisions for the resolution of any future disputes between shareholders. Policymakers should provide a suitable and conducive legal framework to promote new investment and at the same time protect the rights of Afghan entrepreneurs.

Recommendation #5

Sharpen the investment acumen of Afghan entrepreneurs

There are already promising signs of international impact investment firms willing to invest in Afghan companies. In order to speed-up the deal-making process, Afghan entrepreneurs need to know the ins and outs of how to best engage with investors. Starting with the pitch and management presentation to the due diligence process and agreeing on the valuation of the company, there are many pitfalls to be wary of. Investors have usually an edge when it comes to defining the highly-specific details in the shareholder’s agreement such as ‘pre-emption rights’ and ‘rights of first refusal’ or the so-called ‘tag-along and drag-along’ rights or ‘anti-dilution provisions’. Afghan entrepreneurs need guidance and advice from an independent and non-profit organization to avoid spending huge sums to legal advisors. This will enable Afghan entrepreneurs to sharpen their investment acumen and negotiate at a level playing field with their counterparts.

Conclusion

Afghanistan has a long way to go in developing its ecosystem for entrepreneurs and SMEs. Paramount to the success of the ecosystem is a well-formulated guiding strategy upon which all stakeholders can channel and coordinate policies, initiatives and programs. This requires analyzing the current business environment, setting a realistic vision for the ecosystem, and prioritizing initiatives into a roadmap. The implementation of this roadmap hinges upon the collective effort by the Government of Afghanistan, the private sector and the international community. It is a daring endeavor, but also the surest way of delivering on the ANDPF’s promise to attain self-sufficiency for the Afghan economy.

“Turning Afghanistan into an entrepreneurial economy is a daring endeavor, but also the surest way to attain self-sufficiency for the Afghan economy.”

Jussof Breshna